Introducing Project Timestamper

“Do you realize that the past, starting from yesterday, has been actually abolished? If it survives anywhere, it’s in a few solid objects with no words attached to them, like that lump of glass there. Already we know almost literally nothing about the Revolution and the years before the Revolution. Every record has been destroyed or falsified, every book has been rewritten, every picture has been repainted, every statue and street and building has been renamed, every date has been altered. And that process is continuing day by day and minute by minute. History has stopped. Nothing exists except an endless present in which the Party is always right. I know, of course, that the past is falsified, but it would never be possible for me to prove it, even when I did the falsification myself.”

-- Winston Smith in 1984 (George Orwell)

Project Timestamper is an open-source effort to protect the integrity of humanity’s informational heritage in the age of generative AI. By digitally timestamping historical content as it exists in the mid 2020s, we hope to ensure that human generated content of the past can be clearly identified as such even after AI-generated content comes to dominate our culture.

To understand the threat that generative AI poses to the historical informational record, it is helpful to consider how the information economy has evolved since ancient times. The falling costs of generating, reproducing, and transmitting information over time have big implications for those who value our cultural and scientific heritage.

In the far past, essentially all human-consumable text and images were generated by humans. Human cultural records were tightly bound to physical objects such as stone tablets, parchment, cave drawings, paintings, etc. Information was scarce because its generation, reproduction and transmission was very expensive. Any ancient work of literature, art, or science had great value because it was so rare and often written in stone or on expensive parchment or paper. Intellectual property was relatively easy to enforce because it coincided with control of physical property.

The Rosetta stone, the key to ancient Egyptian writing.

The Rosetta stone, the key to ancient Egyptian writing.

As history passed through the popularization of the printing press, photography, audio and video recording, and finally the internet, information has been increasingly less attached to unique physical objects and much cheaper to share. The cost of obtaining meaningful information became dominated by the generation of that content and no longer its reproduction or transmission. As a result of this change in costs, the enforcement of intellectual property, or copyright, has become much more difficult.

Nonetheless, convincing high quality content remained relatively expensive to fake. So the simple existence of a piece of work, if it appeared to be high quality and costly to make, lent that work at least a certain presumption of authenticity.

Now we are potentially entering a third phase of the information economy, where the generation of new content becomes exceedingly inexpensive: generative AIs will be able to produce content at a rate that far outpaces humans. Just as inexpensive reproductive technology made copyright hard to enforce, inexpensive generative technology will make authenticity much more difficult to enforce. The mere existence of a particular artifact will no longer give any weight to its authenticity, because fakes will be so cheap to make. Therefore, knowing what information is meaningful or true will come increasingly to rely on the ability to authenticate that information’s provenance. Who (or what) generated a piece of work, and is that source reliable?

AI generated fake photos of fake humans (by generated.photos)

AI generated fake photos of fake humans (by generated.photos)

Part of this authentication challenge can be met by digital signatures. A contemporary author can cryptographically sign their work with a private key, and a public key can be used to verify the authenticity of that signature. It’s mathematically impossible for an AI (or another human) to fake the signature of the original author, provided they remain in sole possession of their private digital keys.

Traditionally, digital signatures themselves are difficult to use because public keys consist of a series of seemingly random letters and numbers. Blockchain technology can help with this problem, by allowing individuals to “claim” a human-memorable name (such as LeonardoDaVinci) in a way that is secure and universally recognized. By using a blockchain-based naming system such as Namecoin, humans should be able to verify the authenticity of one another’s work at scale in a way that is secure against attacks by an AI.

But this change in the information economy poses a challenge not only to the authenticity of work produced by contemporary authors, but also to historical content produced before digital signatures were available. How can future generations know which is the authentic writing of Shakespeare, or Sun Tzu, or Rumi, if it’s possible to make plausible imitations in copious quantities? How will readers be able to rely on Wikipedia, when it could be edited by AI bots generating millions of plausible, but false, edits to articles or even breaking into the Wikipedia databases and making unauthorized changes to the edit history? How will humans know what happened in history if the historical record becomes heavily polluted by fake documentation? How will future generations recognize an authentic painting when there are thousands of variations of every artist’s work?

Mickey Mouse, by Rembrandt?

Because, historically, humans have relied on the mere existence and complexity of content to infer a certain amount of authenticity, that historical content will now be largely undefended from pollution by generative AI. In order to defend it, we need to find a way to “lock in” existing historical content so that it can’t be mistaken for future fakes.

Again the blockchain comes to the rescue. Using the ingenious service opentimestamps.org, it’s possible to produce an unfakeable timestamp of any content that exists today. The digital timestamp proves that historical content existed at least as early as the date on which the timestamp was made. Any AI-generated content created to falsify historical documents in the future may appear authentic, but it will be impossible to backdate the counterfeit version: any timestamp on documents in the future will necessarily be later than documents that existed earlier.

Any historian in the future will thus be able to use the timestamp information to securely verify that a document from humanity’s cultural heritage existed on or before the date it was timestamped. A timestamp for any content that existed before the advent of AI’s ability to produce convincing fakes thus proves that content was generated by humans.

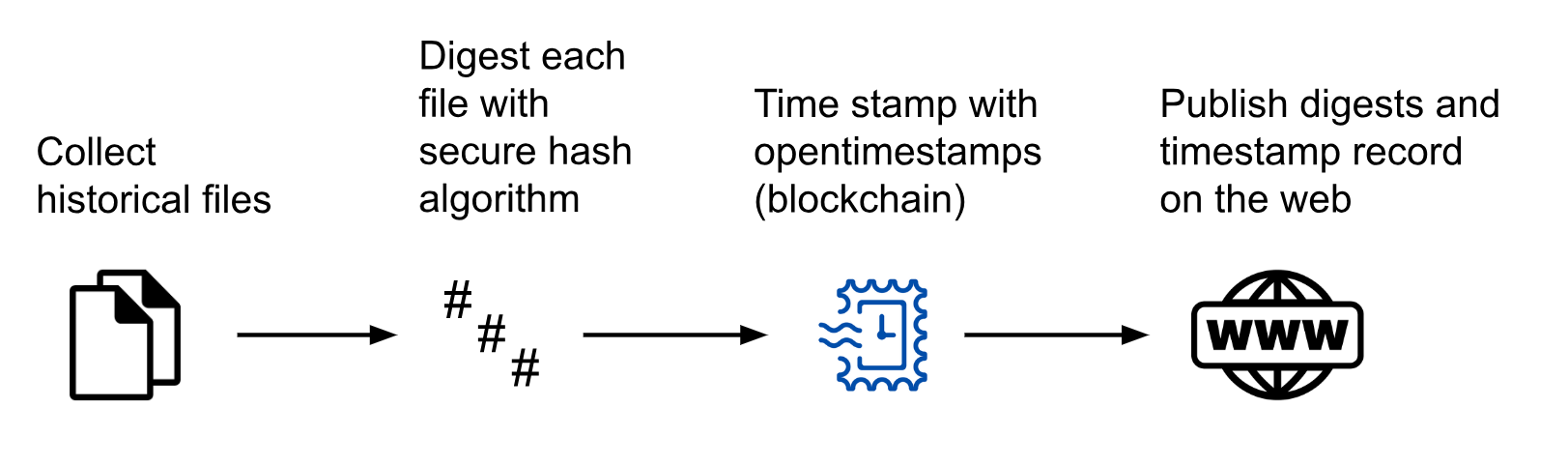

Our automated timestamping procedure works conceptually as follows:

- We select a collection of historical digital files to be timestamped. These files can be text, images, PDFs, database dumps, web pages, or any other digital content.

- We use a secure hash algorithm (such as SHA-256) to produce a digest for each file.

- We submit the digests to the OpenTimestamps service using an opentimestamps client, saving the timestamp record file that is returned.

- We publicly share the digests and timestamp records so that anyone in the future can verify that the files existed on today’s date.

Generative AI is under rapid development today. In the past couple of years, we have seen fast progress in generative AI, and the threat of compromising the integrity of our historical record is growing. For that reason, there is an urgency to timestamp as much valuable historical content as soon as possible, so that future generations can refer back to those timestamps and have a measure of confidence that those historical documents had not yet been compromised at the time that the timestamp was generated.

The goal of our project is to undertake timestamping of a variety of historical data collections of high value density available on the web. So far, we have created a service that automatically time stamps the database dumps of Wikipedia and other Wikimedia Foundation sites, including Wiktionary, Wikibooks, Wikiquote, Wikinews, Wikispecies, Wikiversity and Wikivoyage. Twice a month, Wikimedia Foundation publishes new database dumps of the entire text of all language editions of Wikipedia and these other sites. The timestamper service digests these dumps, assembles them in a manifest for timestamping by opentimestamps.org. The resulting JSON manifests and timestamp record (OTS) files are available here. We have also timestamped all books from the Gutenberg Project.

In addition, we have timestamped fiction and nonfiction books from LibGen, all IMDB-indexed movies found on The Pirate Bay, and all movies from the YTS movie torrents database. We didn’t need to download these materials – instead, digests are already availble for timestamping. (Note that in some jurisdictions, downloading copyrighted books and movies is illegal. However, in the future the copyright for these works of art will have expired and be available for download, so we are generating the timestamps now before generative AI has fully taken over the information space.)

We have also timestamped all the articles in Scihub using existing digests. In the future we hope to timestamp more collections, including the genomes of humans and thousands of other organisms that have been sequenced, digitzed paintings, recorded music, etc.

We hope to encourage institutions that run important archival projects, such as the Internet Archive, Open Library, YouTube, Google Books, and Getty Images, to regularly timestamp the content in their databases as well.

In addition, we hope to make it easy to timestamp YouTube videos, web pages, social media posts, and other historical content that is of value to someone who wants to preserve the integrity of that content for future generations. We also want to make these timestamps easy for the public to find and verify.

We appreciate all support! Code contributions, cooperation and other forms of support are gratefully accepted.